A water district best known for supplying the celebrity-studded enclaves of Calabasas and Hidden Hills could soon become famous for a very different reason.

The Las Virgenes Municipal Water District recently partnered with California-based OceanWell to study the feasibility of harvesting drinking water from desalination pods placed on the ocean floor, several miles off the coast of California.

The pilot project, which will begin in Las Virgenes’ reservoir near Westlake Village, hopes to establish the nation’s first-ever “blue water farm.”

The company says that by combining desalination with off-shore energy technology, it can solve many of the challenges associated with traditional, land-based desalination, including high energy costs and salty byproducts that threaten marine life. The process could produce as much as 10 million gallons of fresh water per day — a significant gain for an inland district almost entirely reliant on imported supplies.

“It gives us a sense of long-term water reliability, but it also gives us the idea that we can really start weathering the storms, if you will, when it comes to climate change impacts, and specifically droughts,” said Mike McNutt, a spokesman for Las Virgenes. “This can be a game changer for Las Virgenes, but it could be a game changer for any water agency anywhere.”

Local environmental groups said the concept seems promising, but not without downsides.

“Our policy is that ocean desalination should always be the last resort,” said Charming Evelyn, chair of the Sierra Club’s water committee in Southern California. “Water is not an infinite resource. It is extremely finite, and the ocean is not something we just get to dip a large straw in and pull whatever we want out, because even the ocean has to maintain a balance.”

The traditional desalination process pumps seawater from coastal areas into facilities on land, where the water is pushed through fine membranes and filters to remove salt and other materials. The process is energy intensive — often fueled by greenhouse-gas-emitting fossil fuels — and produces a thick, briny sludge on the back-end that is typically released back into the ocean. Studies have shown the concentrated brine can be harmful to marine life.

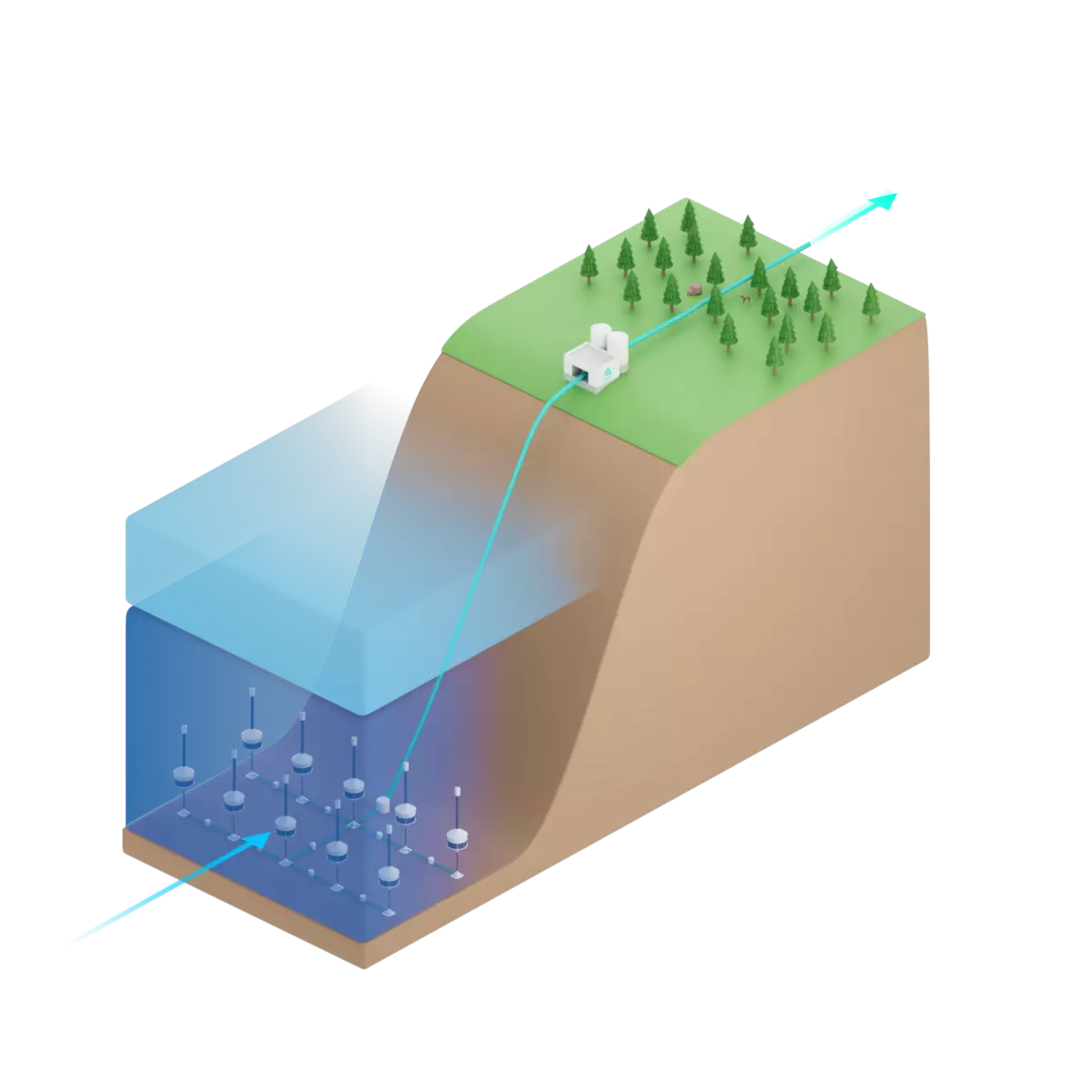

But OceanWell says its technology can use up to 40% less energy by harvesting the water in pods placed at depths of about 1,400 feet, where naturally immense water pressure can help power the filtration process.

“Basically the weight of the ocean helps drive the reverse-osmosis process,” said Kalyn Simon, OceanWell’s director of engagement. “By taking the [reverse-osmosis] process to a place in nature where that pressure naturally exists, we don’t have to create an artificial pressure gauge on land, as we traditionally do in desalination.”

The depth is known as the aphotic zone — a part of the ocean where there is little-to-no sunlight, and where there is less marine life than layers above, she said. Such depths are typically found between three and seven miles off the coast of California, depending on location, which means the project would run through state and federal waters.

The process also produces no brine, Simon said.

Land-based facilities try to squeeze out as much freshwater as possible to help balance high energy costs, with typical targets of 50% freshwater and 50% brine from every gallon processed. But because OceanWell uses “free” pressure from the ocean, it can operate at a lower recovery rate of 10% to 15%, producing a much less salty byproduct that can be dissolved back into ambient conditions within seconds, she said.

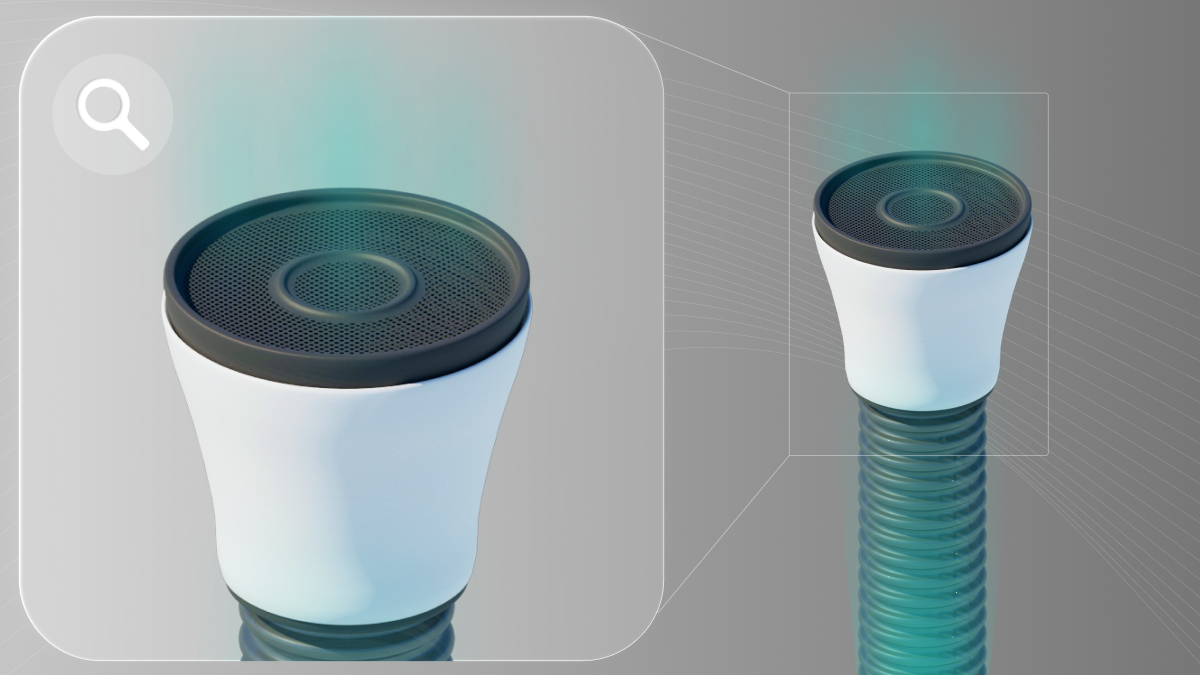

A “farm” would consist of multiple desalination pods — 40-foot wide cylindrical cartridges that contain intake pumps — that draw seawater through a semi-permeable filter membrane. The filtered freshwater would be returned to shore through a pipeline, while the seawater outfall would be discharged from the pods into the ocean through a tall column.

“The solution never has time to settle on the sea floor — it goes into the current,” Simon said. “There are no known effects on the ocean at this low of a concentration, and we will be continuing to do studies and environmental tests to continue to prove that.”

The technology is intriguing, said Mark Donovan, chair of the CalDesal advocacy group, who is also the North American water treatment and desalination lead with GHD, an engineering and consulting firm.

“The concept of putting it down at the bottom of the sea floor, deep enough where that hydrostatic pressure can drive the reverse-osmosis process — there’s certainly merit to that,” Donovan said. And by operating at a very low recovery rate, “it’s true they’re not generating as salty of brine as the traditional, land-based system does.”

Desalination was among the technologies outlined in Gov. Gavin’s Newsom’s water supply strategy, released in 2022 amid the state’s driest three years on record. California is expected to see a 10% decrease in its water supply by 2040 because of higher temperatures and decreased runoff, the governor’s plan said.

Donovan said he sees desalination playing a pivotal role in the state’s response to shrinking water supplies. He was glad to see OceanWell gaining traction with a local water district.

“I think it’s very good for the industry and for California as a whole,” he said.

The Las Virgenes district, which supplies about 75,000 people, is almost entirely reliant on imported water from the State Water Project, a vast network of reservoirs, canals and pipelines that feeds dozens of agencies across the state. But the district faces routine challenges during times of drought, especially when state officials are forced to slash their allocations.

In addition to the OceanWell pilot, Las Virgenes is also moving forward with plans for the Pure Water Project, a wastewater purification facility that will have the capacity to treat up to 6 million gallons per day and boost the region’s supply.

The combination could cut the district’s reliance on imported water in half, according to McNutt, the Las Virgenes spokesman.

“We’re now going to be one of the first to push forward this new technology that could have major impacts on long-term water reliability, with minimal environmental impacts, to the entire state of California,” he said. “Beyond that, we promised our communities after the last drought that we would look into desalination as a possible viable option to provide water to the service area so we wouldn’t go through what we did before.”

Funding for the pilot project will come from OceanWell, with Las Virgenes providing in-kind services, including the use of its 120-foot-deep reservoir for testing the technology.

Las Virgenes prides itself on its forward-thinking ethos, McNutt said. It was one of the first districts to install purple pipe recycling systems in the 1970s, and one of the first to reuse solid waste from its Tapia Water Reclamation Facility. During the most recent drought, the district designed custom flow-restrictor devices to reduce water to wasteful customers.

The OceanWell system “could really revolutionize using Mother Nature to benefit us without having to generate electrical costs and the corresponding greenhouse gas emissions,” he said.

But getting the desalination project past regulators will be a significant hurdle. The California Coastal Commission, the State Lands Commission, the State Water Resources Control Board, the Division of Drinking Water, the Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Army Corps. of Engineers are just some of the agencies that could be involved — as will the general public, which has historically been skeptical of desalination.

Tom Luster, an environmental scientist with the California Coastal Commission, said the concept shows promise but that he is looking forward to seeing more data. Two other companies, SeaWell and Oneka, are testing similar ideas using surface buoys and wave power, but OceanWell was the only one he knew of that wants to place pods on the ocean floor.

“There is a potential that it will have less of an effect on marine life than the shore-side facilities, but we just don’t know to what degree yet,” Luster said. “And then if there is an impact, how do you mitigate for something like that? How do you make up for the loss of deep-sea marine life? That will be a question we may need to answer.”

Evelyn, of the Sierra Club, shared similar reservations about the effects on marine life. The dark aphotic zone is home to plankton and other organisms that could potentially get trapped in filters or experience long-term effects from the brine. “I need to see the numbers and I need to see the science,” she said.

She noted that while the process is less energy-intensive than that of facilities on land, it will still require some amount of energy to push the freshwater from the deep ocean back onto the shore, and to transport it to its final destination. She said conservation, water recycling and stormwater capture are all strategies that should be tried first.

However, Evelyn commended the company for reaching out to the Sierra Club and other environmental groups over the last year, and for taking their feedback and concerns into account while developing the technology.

“I am happy to see that there is new technology and there is less harm to marine life, and that the energy output can be less — I am happy for all of those things,” Evelyn said. “But the other side of me always thinks about the fact that when you pull one string in nature, everything is connected. And I do have concerns about how does this affect us 50, 60, 100 years from now.”

Donovan, of GHD, added that while the aphotic zone may have less marine life, the water there is colder so it could require a bit more energy to drive it through the membrane than warmer waters. “But I think all in all, they’re getting some net benefits by being deep and out in that aphotic zone,” he said.

It could be several years before the project makes it to the sea floor. The partnership with Las Virgenes will allow OceanWell to “stress test” the technology’s capabilities in the reservoir and collect more data, Simon said. The current goal is to be fully operational by 2028, producing an estimated 10 million gallons of freshwater per day.

By comparison, the Carlsbad desalination plant in San Diego County produces 50 million gallons per day, or about 10% of the county’s supply of water. The Doheny desalination plant, approved by the Coastal Commission last year, will produce about 5 million gallons per day in Orange County when it is completed around 2027.

Luster, of the Coastal Commission, said large-scale, open ocean intake projects will continue to have a hard time getting state approval because of their high energy costs and the environmental damage they can cause. The commission last year rejected plans for the proposed Poseidon desalination plant in Huntington Beach due to those and other concerns.

Smaller-scale off-shore systems, such as OceanWell’s, could potentially benefit from a more streamlined approval process if they’re proven to work, Luster said. And while he does not consider desalination a silver bullet for all of the state’s water woes, he said it could play a small part in California’s portfolio moving forward.

“If they can provide water in coastal areas, that frees up water for inland areas,” he said. “And that in and of itself is going to be a good contribution to the state.”

Originally posted in LA Times BY HAYLEY SMITH | STAFF WRITER

Date: SEPT. 19, 2023

Heading